On the cover of Time Magazine.

January 23, 1933

To cure the whole world he prescribes "Japanism"

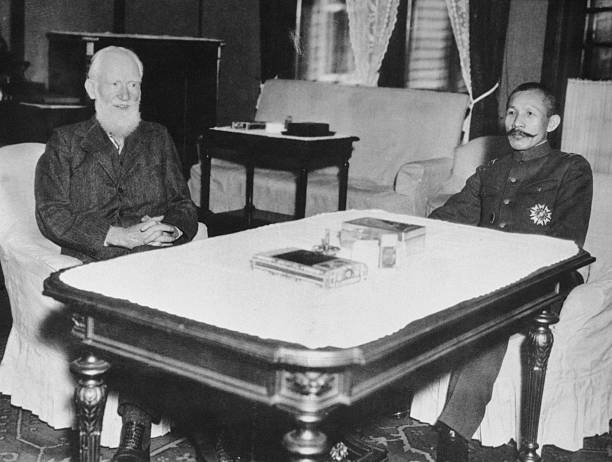

George Bernard Shaw Visiting General Sadao Araki.

March 7, 1933

"He returned to the Sansoms'. At 4 o'clock, accompanied by the British consul, he appeared at the official residence of the Min- ister of War, General Sadao Araki. Shaw's meeting with the general was the most publicized event, and the diplomatic climax, of his sojourn in Japan, although the press accounts of it disagree with one another. The Tokyo Asahi of 8 March has Shaw committing several faux pas: entering the room abruptly, without a word of apology; walking on the tatami- matted floor without removing his shoes, so that his hosts, taken aback, hastened to offer him a chair; and adding lemon and sugar to the Japanese tea that requires no such melioration. (At home he drank no tea.) The Jiji Shimpo of the same date asserts that Shaw began to take off his shoes, but the War Minister told him to keep them on. Similarly, a few of the statements ascribed to one of the two participants in a particular newspaper may be found ascribed to the other in a different paper. "Journalists' Competition Surrounding Shaw" notes that the pair had difficulty understanding each other, and that the official interpreter had even greater trouble trying to fathom Araki's vague language, derived from Buddhist philosophy, than in grasping Shaw's meaning.

Fortunately, an eyewitness account of the interview was submitted to his superiors by Consul Sansom, an observer proficient in Japanese as well as English. Told that General Araki was interested in converting Shaw to his own political viewpoint, and knowing Shaw's tenacious adherence to his own beliefs, Sansom looked forward to a lively session.

We were introduced into a large waiting-room, whither the general, de- tained at the Diet, came after a short delay. The preliminary greetings over, some large double doors were flung open, and there poured into the room a phalanx of press photographers, about thirty of them I should say. The protagonists posed, the air was filled with explosions and disagreeable smoke. High military officers, splendid but deprecatory, made the mildest efforts to control the camera men, who were grinning and snarling like wild beasts. It seemed as if the tumult would never end. The most daring of the photographers mauled the general and Mr. Shaw, poked cameras into their faces and altogether behaved in a dis- graceful way. It was an awful scene, and I could not help thinking that it was characteristic of present-day Japan. The all-powerful militarist leader was quite unable to control this pack of ruffians.

Once free of the photographers, they moved to another room, and settled down round a table. Present, in addition to the general, Shaw, and Sansom, were an interpreter, a Colonel Homma, and "two ridiculously earnest young officers taking notes." The entry of the general's pretty daughter with refreshments interrupted the conversation. "While General Araki attempted to keep the conversation on a high philosophical plane, Mr. Shaw brushed aside his efforts and reverted to his own favorite topics - the futility of war, the blessings of communism and so on." But to everyone's surprise a rapport developed between them, and "they got on together famously. General Araki is a man of great personal charm; Mr. Shaw has a way with him, and they both like a joke. So that the symposium developed into a good-humored exchange of quips, Mr. Shaw scoring most of the points. 'Nervo and Knox, or the Two Macs,' as he put it to me later."

A highlight of the exchange was their jousting on the theme of earth- quakes. The general wanted to know if Shaw had a "philosophy of earthquakes." According to Sansom, this sounded odd to Shaw, who was unaware "that the Japanese, an active and empirically-minded people, are under the mistaken impression that they are a race of philosophers." The Spartan Araki believed that earthquakes were beneficial for Japan. They bolstered the character of the people, helped them develop self-control, and precluded undue attachment to personal lives and possessions. Living with earthquakes taught the Japanese to face calamities calmly. By comparison air raids, of which they could be forewarned, were nothing to fear. He regretted that Shaw had not experienced the recent earthquakes. Shaw asked whether Araki would favor having the War Minister in England plant dynamite in the ground to provide artificial earthquakes periodically. Laughing, the general thought that would be salutary. Shaw conceded England's moral deficiency in this regard, and the inability of the average Englishman to conceive that the solid earth could move. "'But,' he continued, . . . 'we have our earthquakes in England. When people think that their institutions, their religions, their beliefs are firm and immutable, some disagreeable fellow like me comes along and upsets their cherished convictions. Now you need that kind of earthquake in Japan!'" The War Minister viewed with abhorrence the utter materialism of the Soviet regime. Its exclusive concern with food and trade was repul- sive to a spiritual culture, such as that of the Japanese. Shaw's response was that it struck him, during their enjoyable conversation, that the general was the same type of man as Stalin - each of them a man determined to put his ideal into practice. If General Araki were to go to Moscow for a month or so, he would undoubtedly return a dedicated communist. The Japanese army, too, exemplified true communism, for every soldier - rich or poor, big or small - performed his duties on the front in the same spirit, no matter how much he was paid. Communism, he went on, had the motive power of a religion, and, anxious as the Russians were to remain at peace, they would be formidable foes for Japan if war broke out between the two nations. Araki, granting the point, insisted nevertheless that there were irreconcilable differences be- tween the moral standards of the Russians and Japanese, and implied that they might eventually lead to war. He contended that notwithstanding Japanese swings in thought and sentiment from material to spiritual, the pendulum had a secure pivot: the Imperial House. Whatever pivot the nations of the West might have, it struck him as being a fairly slack one.