On June 27, 1907, at the height of a crisis in Japanese-American relations, President Theodore Roosevelt decided to send the Atlantic battleship fleet to the Pacific in the fall. The 1904–5 Russo-Japanese War had demonstrated the military and naval might of Japan, while the decisive Russian defeat at Tsushima impressed on the public’s consciousness that a battle fleet, after steaming great distances, could arrive at its destination in no condition to fight. With nearly all U.S. battleships in the Atlantic Fleet, the U.S. naval force in the Pacific was no match for the Japanese Imperial Navy. Aware of these conditions, West Coast residents of the United States felt vulnerable to attack.

Coinciding with the Japanese-American diplomatic crisis in 1907, the Atlantic Fleet possessed a sufficient number of new first-class battleships available for a sustained exercise. Roosevelt seized the opportunity and ordered the Atlantic battleship fleet deployed to the Pacific Ocean. The exercise would test the new battleships’ mechanical systems and their ability to reach the Pacific in fit condition to engage an enemy as well as bolster the security of the West Coast. On July 2, Secretary of the Navy Victor H. Metcalf announced that “eighteen or twenty of the largest battleships would come around Cape Horn on a practice cruise, and be seen in San Francisco Harbor.”

President Roosevelt’s message precipitated a wave of invitations from countries along the route for the fleet to pay port visits. By this time, diplomatic relations with Japan had also improved as it became clear that the Japanese had no intention of declaring war. The Japanese ambassador extended his country’s invitation, pointing out that a visit by the American fleet to Japan would emphasize the “traditional relations of good understanding and mutual sympathy” between the two countries.

President Roosevelt did not send the battle fleet on its globe-girdling voyage principally to awe Japan. Rather, he intended to exercise the fleet, demonstrate America’s naval prowess to the nations of the world, and garner enthusiasm for the Navy among Americans at home as well as votes in Congress for naval construction. Seen in this light, the first half of the cruise would be an exercise in naval contingency planning, and the second half, an exercise in naval diplomacy at home and abroad.

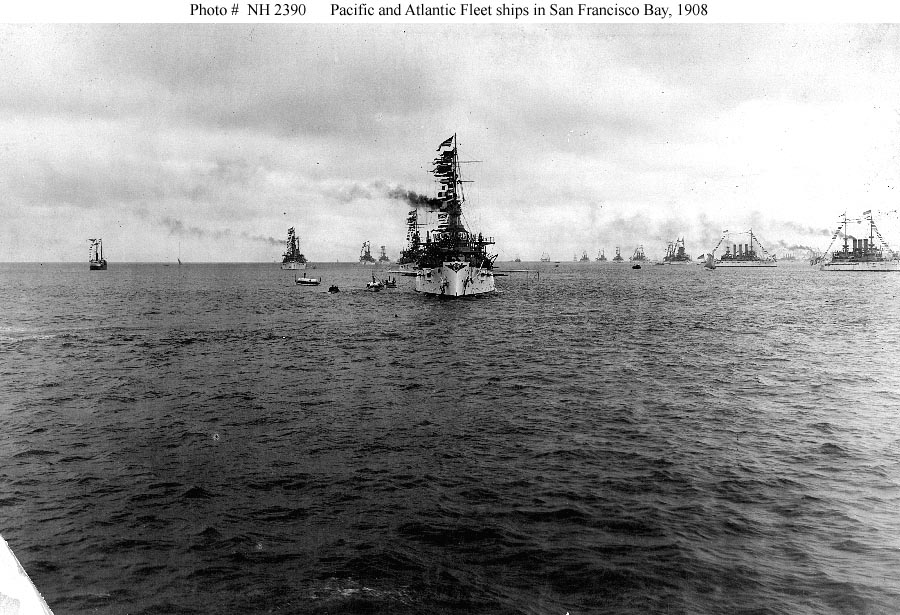

The fourteen-month-long voyage was intended to be a grand pageant of American naval power. The squadrons were manned by 14,000 sailors. They covered some 43,000 nautical miles (80,000 km) and made twenty port calls on six continents. Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry assumed command of the fleet at San Francisco. Leaving that port on 7 July 1908 the U.S. Atlantic Fleet visited Honolulu; Auckland, New Zealand; Sydney, Melbourne, and Albany, Australia; Manila, Philippines; Yokohama, Japan; and Colombo, Ceylon; then arriving at Suez, Egypt, on 3 January 1909.

Coinciding with the Japanese-American diplomatic crisis in 1907, the Atlantic Fleet possessed a sufficient number of new first-class battleships available for a sustained exercise. Roosevelt seized the opportunity and ordered the Atlantic battleship fleet deployed to the Pacific Ocean. The exercise would test the new battleships’ mechanical systems and their ability to reach the Pacific in fit condition to engage an enemy as well as bolster the security of the West Coast. On July 2, Secretary of the Navy Victor H. Metcalf announced that “eighteen or twenty of the largest battleships would come around Cape Horn on a practice cruise, and be seen in San Francisco Harbor.”

President Roosevelt’s message precipitated a wave of invitations from countries along the route for the fleet to pay port visits. By this time, diplomatic relations with Japan had also improved as it became clear that the Japanese had no intention of declaring war. The Japanese ambassador extended his country’s invitation, pointing out that a visit by the American fleet to Japan would emphasize the “traditional relations of good understanding and mutual sympathy” between the two countries.

President Roosevelt did not send the battle fleet on its globe-girdling voyage principally to awe Japan. Rather, he intended to exercise the fleet, demonstrate America’s naval prowess to the nations of the world, and garner enthusiasm for the Navy among Americans at home as well as votes in Congress for naval construction. Seen in this light, the first half of the cruise would be an exercise in naval contingency planning, and the second half, an exercise in naval diplomacy at home and abroad.

The fourteen-month-long voyage was intended to be a grand pageant of American naval power. The squadrons were manned by 14,000 sailors. They covered some 43,000 nautical miles (80,000 km) and made twenty port calls on six continents. Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry assumed command of the fleet at San Francisco. Leaving that port on 7 July 1908 the U.S. Atlantic Fleet visited Honolulu; Auckland, New Zealand; Sydney, Melbourne, and Albany, Australia; Manila, Philippines; Yokohama, Japan; and Colombo, Ceylon; then arriving at Suez, Egypt, on 3 January 1909.