Count Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich /Russian: Граф Михаил Андреевич Милорадович; October 12 [O.S. October 1] 1771 – December 27 [O.S. December 15] 1825[1]/ was a Russian general prominent during the Napoleonic Wars, who, on his father side, descended from Vlach noble family and the katun clan of Miloradović from Hum, later part of Sanjak of Herzegovina, in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. He entered military service on the eve of the Russo-Swedish War of 1788–1790 and his career advanced rapidly during the reign (1796-1801) of Emperor Paul I. He served under Alexander Suvorov during Italian and Swiss campaigns of 1799.

Miloradovich served in wars against France and the Ottoman Empire, earning distinction in the Battle of Amstetten (1805), the capture of Bucharest (1806), the Battle of Borodino (September 1812), the Battle of Tarutino (October 1812) and the Battle of Vyazma (November 1812). He led the reserves into the Battle of Kulm (August 1813), the Battle of Leipzig (October 1813) and the Battle of Paris (1814). Miloradovich attained the rank of General of the Infantry in 1809 and the title of count in 1813. His reputation as a daring battlefield commander (contemporaries called him "the Russian Murat" and "the Russian Bayard") rivalled that of his bitter personal enemy Pyotr Bagration, but Miloradovich also had a reputation for good luck. He boasted that he had fought fifty battles but had never been wounded nor even scratched by the enemy.

By 1818, when Miloradovich was appointed Governor General of Saint Petersburg, the retirement or death of other senior generals made him the most highly-decorated active officer of the Russian army, holding the Order of St. George 2nd class, the Order of St. Andrew, the Order of St. Vladimir 1st class, the Order of St. Anna 1st class, the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky with diamonds. A chivalrous man of boastful and flamboyant character, Miloradovich was a poor fit for the governorship. Vladimir Nabokov called him "a gallant soldier, bon vivant and a somewhat bizarre administrator"; Alexander Herzen wrote that he was "one of those military men who occupied the most senior positions in civilian life with not the slightest idea about public affairs".

When news of the death of Alexander I reached Saint Petersburg, Miloradovich prevented the heir, the future Emperor Nicholas I, from acceding to the throne. From December 9 [O.S. November 27] to December 25 [O.S. December 13] 1825, Miloradovich exercised de facto dictatorial authority, but he ultimately recognised Nicholas as his sovereign after the Romanovs had sorted out their confusion over the succession. Miloradovich had sufficient evidence of the mounting Decembrist revolt, but did not take any action until the rebels took over the Senate Square on December 26 [O.S. December 14] 1825. He rode into the rows of rebel troops and tried to talk them into obedience, but was fatally shot by Pyotr Kakhovsky and stabbed by Yevgeny Obolensky.

At 8 p.m. on December 25 [O.S. December 13], Nicholas declared himself emperor; at 7 a.m. the next morning, along with all senior statesmen present in Saint Petersburg, Miloradovich pledged his loyalty to Nicholas (Korf suggested that Miloradovich recognised Nicholas as early as December 24 [O.S. December 12]). Once again Miloradovich assured Nicholas that the city was "perfectly tranquil"; Alexander von Benckendorff other witnesses wrote that he was in his usual boastful, optimistic mood. Three hours later when Miloradovich enjoyed breakfast with Teleshova, general Neidhardt reported to Nicholas that the troops were marching towards the palace "in absolute mutiny".

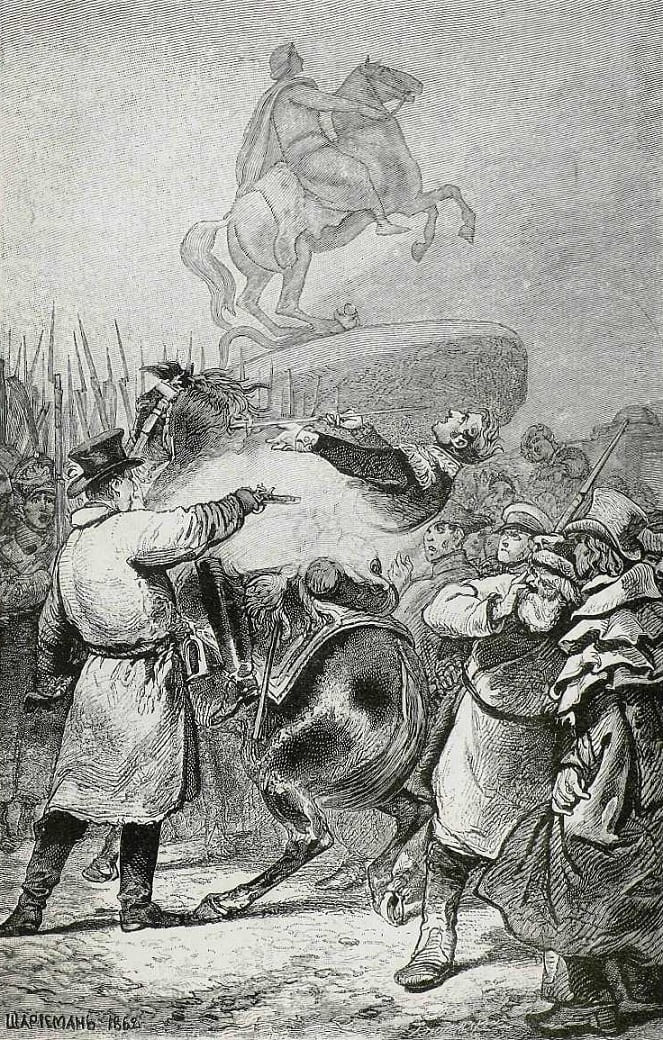

At about noon on December 26 [O.S. December 14] Miloradovich, whom nobody had seen since the morning, reported to Nicholas on Palace Square. Witnesses disagree on whether he was mounted or on foot, but all accounts point to his extraordinary excitement and loss of self-control. According to Nicholas, Miloradovich told him: "Сеlа va mаl; ils marchent au Sénat, mais je vais leur раrlеr" (French: "That is bad; they are marching toward the Senate, but I will talk to them").Nicholas coldly responded that Miloradovich must do his duty as the military governor and calm his troops down. Miloradovich saluted, turned around, and headed to the barracks of the Mounted Guards. General Orlov of the Mounted Guards pleaded with Miloradovich to stay with the loyal troops but Miloradovich refused to take cover, mounted a horse and rode out to the rows of rebel troops, accompanied either by two aides or only by Bashutsky on foot. Miloradovich harangued the soldiers for obedience, showing Constantine's sword "to prove that he would have been incapable of betraying him". Safonov pointed out that, instead of executing the tsar's order to lead the Mounted Guards against the rebels, Miloradovich "disobeyed it in a most incredible way ... by going into the action alone."

Between 12:20 and 12:30 Pyotr Kakhovsky shot Miloradovich point-blank in the back; "the bullet travelling up from below, from the back to the chest, tore the diaphragm, broke through all the parts and stopped beneath the right nipple". When Miloradovich slumped from his horse to the ground, Yevgeny Obolensky stabbed him with a bayonet. Miloradovich was taken to a nearby house, but by the time the surgeons arrived on the scene the marauders had stripped Miloradovich of his clothes, medals and jewelry. Medics removed the bullet (it was later delivered to Nicholas); Miloradovich remained conscious and dictated his last will in a letter to the tsar. There were three requests: to send His Majesty's regards to his relatives, to grant liberty to his serfs, and to "not forget the old Maikov". Miloradovich died around 3 a.m. on December 27 [O.S. December 15]. After six days of lying in state, he was buried with honors at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

The investigation of the Decembrist revolt led to the hanging of Kakhovsky and four of his ringleaders; it did not reveal any illicit connection between the Decembrists and Miloradovich. The second killer, Obolensky, was stripped of his princely title and exiled to Siberia for thirty years.