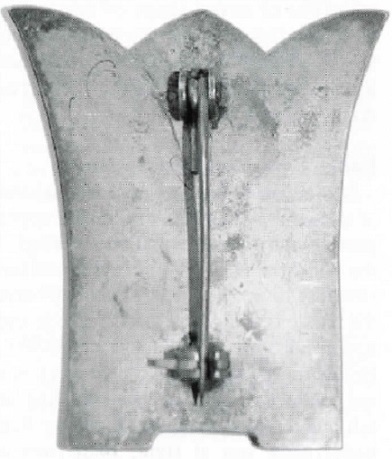

Size 40 x35 mm in widest part (23 mm in the narrowest part).

Obverse

日獨青少年團交驩 - Japan-Germany Youth Group Fraternization /exchange of courtesies (cordialities)/

In German version inscription 日獨青少年團交驩 were translated as Japanisch-Deutscher Jugendaustausch - Japan-Germany Youth Exchange

2600 = 1940

Obverse

日獨青少年團交驩 - Japan-Germany Youth Group Fraternization /exchange of courtesies (cordialities)/

In German version inscription 日獨青少年團交驩 were translated as Japanisch-Deutscher Jugendaustausch - Japan-Germany Youth Exchange

2600 = 1940

The Tripartite Pact linking Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan was signed in Berlin on September 27, 1940. Less than two months after the pact was signed, a six-member delegation of Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth) arrived in Japan. This was actually the second Hitler Jugend delegation to visit Japan, a much larger delegation having first visited in the fall of 1938. In honor of the first delegation's visit, a song was composed entitled Banzai Hitorā Jūgento (Long Live Hitler Youth!). Members of the second delegation traveled to Daihonzan Eiheiji for an overnight stay on November 19, 1940. Eiheiji, located in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture, was established by Zen Master Dōgen, the founder of the Sōtō sect, in 1244 and is now one of the two head monasteries of the Sōtō sect, Japan's largest Zen sect. The accompanying photograph shows the Hitler Jugend seated in the front row surrounded by Eiheiji's senior monastic officials, including the head of the monastery seated in the center. It was taken shortly before the delegation departed the monastery on the morning of November 20, 1940.

The August 1942 issue of the Eiheiji periodical Sansho included an article describing the instructions Hitler had personally given the delegation prior to departure:

When you are in Japan, there is no need for you to be concerned about Japanese culture.

There is no need for you to research Japanese politics. There is no need to investigate Japan's economy.

The only thing you need do is thoroughly experience the great spirit of the Japanese people that has arisen in their national polity.

To understand why Hitler so strongly emphasized the need for German youth to understand "the great spirit of the Japanese people," we should recall that as early as his 1925 work Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote: "All force which does not spring from a firm spiritual foundation will be hesitating and uncertain." Hesitating and uncertain force was the last thing Hitler needed in his future soldiers.

As far as Eiheiji's leaders were concerned, there was no better place to learn the great spirit of the Japanese people than their monastery. In the same August 1942 article, Eiheiji's head monk trainer, Zen Master Ashiwa Untei, described Eiheiji's importance and its relationship to the young Nazis' visit:

Someone has said that Asia as a whole can be described as a training center for the human spirit. Europe, on the other hand, can be described as a learning center for the cultivation of knowledge. A characteristic of Asian spiritual culture is the training of the human spirit through the practice of zazen [seated meditation] and sitting quietly. It is for this reason that the latent energy of spiritual power grew out of Asia acting as a training center for disciplining the human spirit. . . . The foundation of a nation's destiny, like the development of a person, depends on the power of the human spirit. The training of the human spirit, the importance of vigorous spiritual power is something the citizens of Japan are now selflessly demonstrating to the world. In the late autumn of the year before last, Hitler Jugend visited Eiheiji and stayed overnight. They were profoundly impressed by the existence of the training center for the human spirit they encountered here in the deep mountains.

An even earlier article in the December 1940 issue of Sansho gave a detailed description of the delegation's visit. Appropriately, the article was entitled Hittorā Jūgento (Hitler Jugend). Inasmuch as it reveals important features of the values and religious outlook of both Nazi youth and Japan's wartime Zen leaders, a complete translation follows. Note, however, that the following article presents a necessarily shallow understanding of the spiritual orientation of Nazi youth on the Japanese side inasmuch as it was gained from only one relatively short encounter, not to mention the need for interpretation.

The August 1942 issue of the Eiheiji periodical Sansho included an article describing the instructions Hitler had personally given the delegation prior to departure:

When you are in Japan, there is no need for you to be concerned about Japanese culture.

There is no need for you to research Japanese politics. There is no need to investigate Japan's economy.

The only thing you need do is thoroughly experience the great spirit of the Japanese people that has arisen in their national polity.

To understand why Hitler so strongly emphasized the need for German youth to understand "the great spirit of the Japanese people," we should recall that as early as his 1925 work Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote: "All force which does not spring from a firm spiritual foundation will be hesitating and uncertain." Hesitating and uncertain force was the last thing Hitler needed in his future soldiers.

As far as Eiheiji's leaders were concerned, there was no better place to learn the great spirit of the Japanese people than their monastery. In the same August 1942 article, Eiheiji's head monk trainer, Zen Master Ashiwa Untei, described Eiheiji's importance and its relationship to the young Nazis' visit:

Someone has said that Asia as a whole can be described as a training center for the human spirit. Europe, on the other hand, can be described as a learning center for the cultivation of knowledge. A characteristic of Asian spiritual culture is the training of the human spirit through the practice of zazen [seated meditation] and sitting quietly. It is for this reason that the latent energy of spiritual power grew out of Asia acting as a training center for disciplining the human spirit. . . . The foundation of a nation's destiny, like the development of a person, depends on the power of the human spirit. The training of the human spirit, the importance of vigorous spiritual power is something the citizens of Japan are now selflessly demonstrating to the world. In the late autumn of the year before last, Hitler Jugend visited Eiheiji and stayed overnight. They were profoundly impressed by the existence of the training center for the human spirit they encountered here in the deep mountains.

An even earlier article in the December 1940 issue of Sansho gave a detailed description of the delegation's visit. Appropriately, the article was entitled Hittorā Jūgento (Hitler Jugend). Inasmuch as it reveals important features of the values and religious outlook of both Nazi youth and Japan's wartime Zen leaders, a complete translation follows. Note, however, that the following article presents a necessarily shallow understanding of the spiritual orientation of Nazi youth on the Japanese side inasmuch as it was gained from only one relatively short encounter, not to mention the need for interpretation.